Behind the Scenes at Oxford

[av_one_full first min_height=” vertical_alignment=” space=” custom_margin=” margin=’0px’ padding=’0px’ border=” border_color=” radius=’0px’ background_color=” src=” background_position=’top left’ background_repeat=’no-repeat’ animation=” mobile_display=”]

DCI Fellows from all six cohorts participated in the first Stanford at Oxford program hosted by Professor Jane Shaw in early August. Front row (l-r): Jean Collier Hurley (2015), Susan Nash (2017), Mary Ittleson (2017), Fred Martin, Cynthia Cwik (2018/19), Roberta Katz, David Epstein (2019), Jane Shaw (Oxford), Tushara Canekeratne (2017), Ann Stanton (2016), Leslie Hume and Susan Johnson (2017). Back row (l-r): Chuck Katz (2015), George Hume (2107), Melissa Froland (2018), Charles Froland (2018), Sarah Ogilvie (Oxford), Robert Haddock (2016), Greg Davidson (2018/19) and Carl Johnson (2017).

“In watching Measure for Measure, there are three moments you’ll want to look for,” Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Oxford University and Fellow of Hertford College, told us before we boarded a bus for Stratford-Upon-Avon. “Especially for the unanswered question at the end.”

She was speaking of Shakespeare’s immensely relevant tragicomedy, written in about 1603 or 1604, with its ties to the #MeToo movement and its delicate handling of questions of justice, law enforcement and morality. Her lecture was just part of the rich experience that Professor Jane Shaw, Principal of Harris Manchester College, Former Dean for Religious Life at Stanford and DCI Advisor Extraordinaire, created for a group of 18 Stanford DCIers from across all six cohorts who spent a week in August attending “Oxford Then and Now.”

I had little idea what to expect when I signed up. I had been to Oxford once, for a day, and to England quite often, so I imagined that some combination of old buildings, roast meats and puddings would be on the menu. What I got was a diet of a much deeper and more complex fare — a behind-the-scenes look at Oxford’s colleges, museums, libraries and the hard to locate but ever-present “University.”

On Day One, William Whyte, Professor of Social and Architectural History at St. John’s College, led us on a walking tour while lecturing on the history of the University and its colleges. Although the colleges started out as student living accommodations, by the Middle Ages each college had acquired its own chapel, dining hall, teaching staff, funding sources and character, so much so that those looking for the “University of Oxford” today must content themselves with hats and sweatshirts bearing that title; even Professor Whyte, who as far as I could tell knows every inch of Oxford and every year of its history, could point to no main quad or gathering place as the University’s center.

To see the real Oxford requires going behind the college walls, access magically granted with our Harris Manchester ID cards, persuading even the prim porters at Christ Church College to admit us with a smile. At New College (founded in 1379) we toured the wine cellar, where 17,000 of the 50,000 bottles are replenished every year for the enjoyment of the “Fellows” or “dons,” as the professors are known. Dons, as anyone who has seen the movie “Tolkien” will know, are also permitted to walk on the college lawns, while students must keep off. It must have been the sampling of the cellar’s wares that persuaded us (at the suggestion of an Oxford don who shall remain nameless) to ignore the “keep off the grass” signs, plant ourselves in front of a staircase leading up to a tree-covered mound, clap our hands, and see what happened. And we did. But, what happens on the mound stays on the mound…

We used our passes to walk in the Deer Park of Magdalen College (pronounced “Maudlin” for reasons no one could explain), on an island in the middle of the River Cherwell. During our free time some went off on their own to explore Worcester College or St. John’s or Balliol (one of the oldest, although there is, of course, a dispute about the order in which the colleges were founded). Signs on the street announced that candlelit Tudor music would be offered that week at one college, jazz at another; we would have needed another month to visit all 38 (or is it 39?) of these unique places.

Over dinner at Rhodes House, Oxford’s Vice Chancellor (read, President and Provost combined, as the “Chancellor” is just an honorary position) Louise Richardson spoke freely about the challenges of running an elite institution amid rising populism and the impending and uncertain effects of Brexit on Oxford’s faculty, staff and students. Before dinner we walked through the carefully tended wildness of the Rhodes gardens. Even this well-respected institution can’t overcome the abundant reverence for history: the grounds superintendent pointed out that a large pile of dirt in the middle of the gardens remains untouched because it is part of the earthworks in which Charles I sought refuge during the English Civil War.

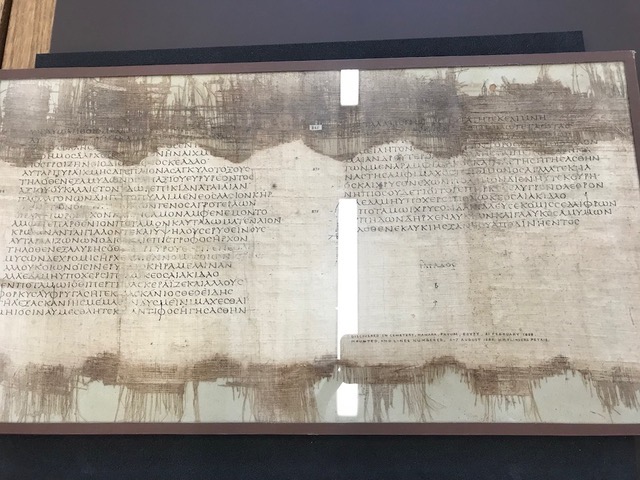

Anyone can visit the Bodleian Library, as I did several years ago, but few get to take an underground tour or see the favorite treasures of five senior curators, ranging from an excerpt of The Iliad on a scrap of papyrus to the 20 serialized editions of Dickens’ Bleak House issued from March 1852-September 1853, to Japanese fairy tales (including the irresistibly titled “Lord Bag O’Rice”) printed in English on crepe paper over a hundred years ago.

The Iliad on papyrus, 2d Century C.E.

At the Oxford University Press we squeezed into a tiny room bulging with card catalogues and thumbed through the millions of slips of paper used by the Oxford English Dictionary to document the history and use of every word ever printed in the English language. Finding myself in the “Ol” drawer, I came across “old and bold,” a majestic reference to retired Naval officers called back to serve in times of war.

DCIers thumbing through the Oxford English Dictionary slips.

At the Natural History Museum we trekked up the back stairs to peer at Darwin’s crustaceans – the actual specimens piled onto the HMS Beagle – and visited the research room where Maria Sibylla Merian’s lifelike illustrations of insects and plants were laid out for us. (Merian could have been a DCI poster child for lifelong curiosity: an “artist, scientist and adventurer” who, in 1699 at the age of 52, embarked with her daughter on a 5-year expedition to Suriname to explore new species.) We finished the visit with an up-close look at the real Oxford Dodo, too fragile to be out in the display case where sits instead the stuffed version that is the basis for our cartoon-like view of this now-extinct flightless bird.

At Blenheim Palace the resident archivist – a benign title for a job requiring the sifting of centuries of material– showed us her prize discovery just a few years back: an actual account submitted by Sarah, first Duchess of Marlborough, and signed by Queen Anne. Although some of us thought we might know these characters from “The Favourite,” questions as to the movie’s historical accuracy were greeted with a throat-learning “ahem” by our guide; what the historical record does show are Sarah’s still-incisive musings on love, friendship and human nature. Reading that friendships are most “perfectly” formed by “those that have some maturity of years and some experience of the world” and that “it is impossible for wicked people to bee [original spelling] happy” made me wish I could sit down with this woman for a cup of tea and a chat.

In the evenings we returned to our “dormitory” lodgings at Harris Manchester, which, unlike my own undergraduate dorm experience, included an en suite bathroom and an expansive view of the college lawn. We had excellent meals served in college with nary a roast beast in sight, except in the tapestries and wood carvings adorning the Gothic halls. The six cohorts blended seamlessly, bonding over big ideas and small glasses of port. Occasionally Jane suggested we “smarten up” before leaving the college to go out for dinner, possibly concerned that we would show up in the Renaissance Gallery of the Ashmolean Museum to listen to harpsichord music in Stanford sweats.

So, now, what to make of this experience and how to carry it forward? How to distill seeing works from the second century to the present, having access to an infinite collection of knowledge from every corner of the planet, creating a bond that reaches across from Stanford to the roots of an Oxford humanities education, and being part of a group that, like the individual DCI cohorts, will itself reune to remember a remarkable time? Toasting Jane and her staff at the end, I plagiarized a page from the Blenheim archives (“this happy trip we’ll ne’er forget, nor the pleasure that it gives”). But like the twist at the end of Measure for Measure, I’m still thinking about it all and don’t have an answer for these questions yet. So I’ll crib again, from Shakespeare, and say, of the Oxonian treasures and offerings: “Let me hear you speak farther. I have spirit to do anything that appears not foul in the truth of my spirit.”

Stanford DCI Visits Oxford will be offered again from August 2-9, 2020.

Stratford-Upon-Avon provided a tranquil walking break for DCIers.

[/av_one_full]